Part 2: The research saga of an expat couple living in Cuenca

Author’s note: This is the second of four articles about how lifestyle changes can reverse heart disease and cancer without drugs or surgery. In the first article, the author described his meeting with Dean Ornish, MD, who had conducted a pilot study that provided the first clue that lifestyle changes might increase the blood flow to the heart muscle. In this article, the author describes his own experience and the results of a study designed to answer the question, “Can a short term of intensive lifestyle change improve the heart’s ability to pump blood?”

- Part 1: Lifestyle and health: The saga of a research couple living in Cuenca

- Part 2: The research saga of an expat couple living in Cuenca

- Part 3: Lifestyle and health: The saga of a research couple living in Cuenca

- Part 4: Lifestyle and health: The saga of a research couple living in Cuenca

By Larry Scherwitz, PhD

A diet for heart health.

Dean Ornish’s guru, Swami Satchinanda, said you don’t need drugs or surgery to treat heart disease. A lifestyle change, the same as yogis have used for centuries to achieve self-realization, will do the job. Dean believed his guru’s advice and took a year off from medical school to conduct a pilot study with nine heart disease patients. Amazingly, their chest pain eased or disappeared, their weight and cholesterol decreased, and two patients who had nuclear medicine scans provided evidence of increased blood flow to their heart muscle. Dean’s confidence was sky-high.

As research mentor, it was my job to point out the weaknesses of the work he had done, and provide the criticism that would make his results accepted by medical professionals.

I explained to Dean that it would take a clinical trial to convince anyone that something as simple as lifestyle change could reverse heart disease. This clinical trial must randomize patients to two groups with—one that made lifestyle changes and the usual treatment control group. Both groups would need the same tests before and after the experimental group made lifestyle changes. My greatest concern was avoiding what researchers called a type 2 error—an error of missing the effect of the treatment itself. A type 2 error would be fatal to Dean’s whole enterprise. If you missed the treatment effect in the first clinical trial you’ve shot yourself in the foot; you are worse off than if you had never done the study at all. You’ve provided evidence that your treatment did not work and you may never get the chance to try it again.

To avoid missing the treatment effect, I worked to make sure the measurements were as accurate and reliable as possible, and even more importantly, I pressed continually for having the research participants make extreme lifestyle changes. Why the extreme changes? Because we did not know how much lifestyle change was required to show a significant improvement. We were also afraid that the control group would make lifestyle changes as a result of being involved in the study, and that would reduce the differences between the two groups.

What Dean and I came up with was a classic study, but at the time, it seemed to me, impossible to conduct. What made it work was a series of miracles combined with a lot of hard work.

Miracle one was finding the heart patients. Houston’s gigantic medical center housed two large hospitals that had cardiac surgical teams that had pioneered coronary artery bypass graft surgery, so almost every heart patient with chest pain and blocked arteries went off to surgery and therefore would not be candidates for our study. In the evenings, we combed through more than 10,000 patient charts from various hospitals and private practices to find 125 patients with at least one coronary artery that was 50% or blocked. Of these, 48 volunteered for the study. Whew!

A second miracle was Dean’s locating free lodging for a retreat. Dean found a real estate developer who had just completed a condominium complex on Lake LBJ, near Marble Falls, Texas. Not yet inhabited, Dean asked the developer for a month’s lodging for 24 heart patients, their spouses, and staff. How nervy! Dean’s negotiations with the developer gave us 24 days. It was a big break to have the free space, but it added more pressure to achieve a result with less time than we had planned.

Yoga was a key component of the program.

A third miracle was getting faculty to agree to do the testing for free. Dean doesn’t take no for an answer; he convinced them by the early results of the pilot study and engaging them as collaborators. Most impressive was that we could use the most sophisticated test available at the time, a radionucltide ventriculogrophy, which showed how well the heart could pump blood in response to exercise.

Dean also brought together an accomplished yoga teacher, herself a physician, a well-regarded vegetarian cook, and my wife Deborah Kesten as nutritional director. At that time Deborah was a Masters Student at the University of Texas School of Public Health. Deborah directed the nutrition and did nutritional analysis of the subjects’ diets, testing for such things as vitamins, fat and cholesterol intake. She made the first finding, later replicated, that when you eat a no fat added diet of vegetable and fruit, beans and legumes, whole grains, and seeds, you get around 10% of fat from total calories. It was amazing to discover that all produce, even lettuce, contains a certain amount of fat.

At this point the research project needed financial grease to keep it running. There were many project expenses that could not be donated. Dean’s personal debt was beginning to pile up, but he refused to quit. It was at this point that we received $50,000 donation from a donor who Dean had personally trained to make lifestyle changes. It was this donor’s gratitude and Dean’s persuasiveness that kept the project on track.

Convincing Texans to give up meat was a challenge. One study participant was the champion of the Super Bowl of Texas chili cooking. They all knew they had a choice: either give up meat or maybe get their chest cracked open for the brutal bypass surgery so popular in Houston. Dean continually stressed that bypass surgery did not get to the original cause of the problem, and if it were done, may have to be repeated. The two hours per day of yoga-based stretching, deep relaxation, breathing techniques, and meditation was an eye-opening and inspiring experience for these patients and the bonds they made in the social support hours was beyond everyone’s expectation.

At the conclusion of our 23-days project, we made by far the most comprehensive and intensive lifestyle changes any research group had ever reported!

At that point, getting the 48 heart patients back to the medical center without going off their diet, and showing up on time for testing was my job. I accompanied the patients through the entire pre- and post-testing battery, so I could talk with each one personally to find out how they were feeling. I was excited since I knew that on a personal level this program had made a transformative impact. My job was to round up all the test numbers while preventing any perceived or real bias. Because those who had made the intense lifestyle changes were so enthusiastic I had to caution them not to tell anyone doing the medical testing that they were part of the group that made lifestyle changes.

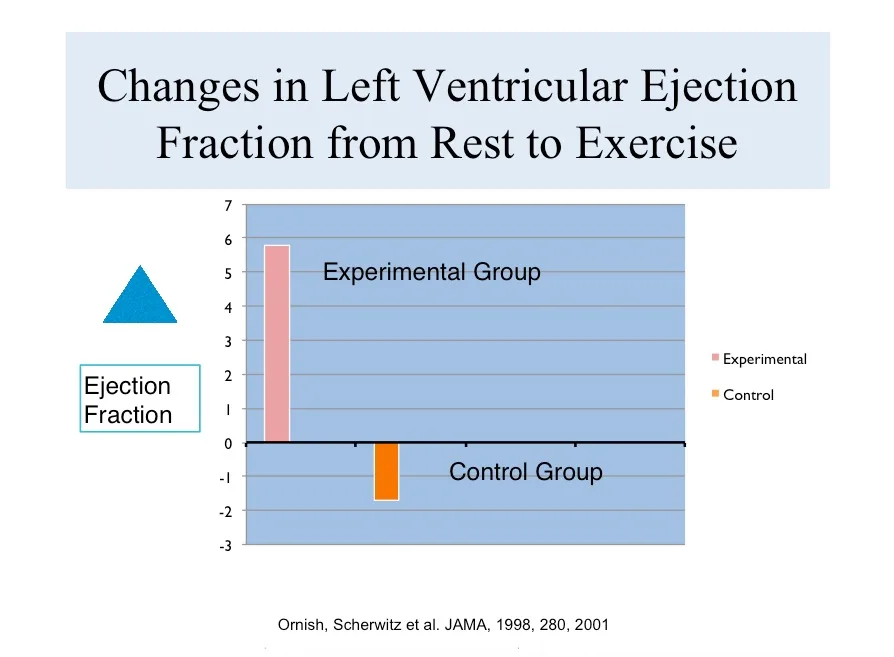

My job was to enter, edit, manage, and analyze the data, so I was the first one to view the results and savor their impact. Those making lifestyle change were flying on the treadmill; they could do 55% more exercise than before the project began. Their cholesterol dropped 21% and the number of times they had chest pain dropped by 91%. The most crucial test was the heart’s ability to respond to exercise; they improved 6.4% compared with 2.0% drop in the control group.

All these findings showed a statistically significant improvement of the lifestyle change group. We did so well in conducting the study that we succeeded in getting the results of the study published in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association. To read the article, click here.

Following the publication of the clinical trial results, the critics said two things. 1) Yeah, you got these changes when you had patients sequestered on a lakeside resort, but you can’t get anybody to follow this program on a free-living basis. 2) You got short-term changes in heart function but there is no proof that you have changed the blockages in blood flow in the coronary arteries.

Part 3 of this series takes us to San Francisco to see the study we designed and conducted to answer these questions.